Blurred Lines: The Uneasy Relationship Between Sex and Pop Culture

- Nik Heimach

- On September 5, 2013

Sex and pop culture are two of the most easily discernible, yet confounding of all foundational aspects in American society. Pop culture (and all cultural expression) helps dictate the national zeitgeist and how we interpret the society around us. It’s existed since the dawn of art, but putting sex in the cultural spotlight is a relatively recent new phenomenon for American audiences.

The counterculture boom of the 60’s and 70’s radiated sex, drugs and rock and roll, opening up entire publics to the rhetorical power of the taboo. From there, sex became a communicative powerhouse. It was used to liberate, it was used to express, but perhaps most significantly, it was used to sell.

Pick up any copy of Cosmopolitan today, and I guarantee the word SEX pops more prominently than any other in the publication’s history. And that’s okay. Directors film it, authors write it, artists paint it and photographers capture it as often as birds and bees do it. After all, sex is a natural phenomenon.

Our perception of cultural promiscuity, however, is not without its parameters.

In order to “maintain levels of decency and protection from the perverse,” the United States Supreme Court developed what became known as the Miller test. Developed in 1973, the Miller test was created as a means to define a piece of work as “obscene.” If a work describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way, appeals to the prurient interest of a community standard, and lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value, it is labeled “obscene,” and therefore forgoes protection by the First Amendment to the Constitution.

What we’re left with, culturally, is a grey area of how sexuality can be depicted to adults (+18). Sex and pop culture are a coupling plagued by competing forces: fear and celebration, prudence and indulgence, chastity and fornication, life creation and pleasure manifestation. This uneasy relationship leads us to the forefront of a metaphorical orgy of ideas. Religion, ethics, feminism, capitalism and art all come together to celebrate or condemn sexuality in culture, creating a rhetorical situation that figuratively erupts society when the blurred lines are crossed on a national scale.

What we’re left with, culturally, is a grey area of how sexuality can be depicted to adults (+18). Sex and pop culture are a coupling plagued by competing forces: fear and celebration, prudence and indulgence, chastity and fornication, life creation and pleasure manifestation. This uneasy relationship leads us to the forefront of a metaphorical orgy of ideas. Religion, ethics, feminism, capitalism and art all come together to celebrate or condemn sexuality in culture, creating a rhetorical situation that figuratively erupts society when the blurred lines are crossed on a national scale.

It’s time to take a step back, look at the bigger picture, and analyze the situation.

Why do we interpret expressive nudity as improper? Where is the line between artful expression and shame exploitation in the court of cultural opinion? Why does merely talking about sex, expression, sensuality, men, women and everything in-between seem indecent to so many?

For what follows, it’s more than fair to acknowledge that I am a white male, and I recognize how my gender and participation in the male gaze potentially impact the following analysis. My hope is that a look into this slice of the cultural pie offers some value in determining how and why the uneasy relationship between sex and pop culture exists as it does today.

Take Exhibit A: Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines.” Warning: Nudity. (The non-nude version is here)

“Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines is a Billboard Chart topper.”

“Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines celebrates sex.”

“Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines promotes rape culture.”

“The girls are sluts.”

“Robin Thicke is a sexist pig.”

These varied responses to Thicke’s music video and the popularity of the song itself represent our potent connection to sex in pop culture. Typically, a breadth of reaction like this happen when sexualization violates personal expectations of how men and women should present themselves in less-sexual spaces, in this case, YouTube. However, it’s also brought on by controversy, particularly in interpretations that see the art in question as harmful. In the case of Blurred Lines, it’s both.

The consensus take is that Blurred Lines objectifies women, parading them around naked and wonton for fully clothed men singing about how, “they want it.” It’s all but confirmed that the “blurred lines” Thicke sings about are the lines between “yes” and “no” in a sexual situation, thus expanding upon the masculine notion that rape is “okay” as long as they “know you want it.” Admittedly, it’s hard to see the lyrics as anything but problematic at best.

If cultural critique weren’t subjective, our lines wouldn’t be blurred at all. We’d know what’s acceptable to show, what one thing stands for and what another denotes, and we would collectively accept or deny entertainment on those standards. But it is, and observing that subjectivity leads us a little closer to understanding why culture and sex are in such a volatile relationship.

Those who see Blurred Lines as gratuitously sexist see it through the framework of patriarchal limits historically placed on women. Traditionally, women are presented in terms of their sexual relation to men, and continuing to do so perpetuates a male-dominated status-quo. It’s why women in media are subjected to sexual objectification, bodily commodification, and hegemonic standards of acceptability in a culture built around straight men. But the sex/culture dilemma in art is not solely determined by its relation to heterosexual men.

“Whose slut?” a brilliant short essay published by The F-Word, argues that the sexualization of women “can be something women can accept, reclaim, and use to liberate themselves from society’s oppressive sex taboo.”*

“The notion that a sexualized woman is degrading to women derives from the assumption that she is being sexualized by men, for men. Historically, this has usually been the case, and the misogynistic religious moralists, whose views are often reflected in pop culture, reinforce this power dynamic at every opportunity. TV stations and magazines use women’s bodies to increase ratings and sell products while taking a moralizing or patronizing stance on those who do, i.e. strippers and prostitutes. We are beginning to show that sexualization can be as fun and empowering for the ones being watched as for the ones watching. Pop icons like Courtney Love and Madonna deliberately sexualize themselves to play with and subvert society’s virgin/whore complex. Anti-porn advocates may be searching for a more ‘authentic’ sexuality but, without a clearer idea of what this might be, their cries of ‘degrading to women’ are merely adding to the common assumption that any woman who enjoys the male gaze must be either a victim or a slut.”

If we try to conceptualize Blurred Lines through this lens as an interpretive exercise, the unrated Blurred Lines video can then be seen through a completely different context.

Viewed without the limitations of how we assume women should look/behave, these mostly naked women are engaged in a seductive pseudo-dance with their clothed counterparts, who can be viewed as too repressed by masculine norms to embrace their natural form and beauty. The camera angles never reduce the women to body parts without facial expressions, nor do the men excessively grope or otherwise impose themselves upon the women. The eye is even meant to follow them instead of Thicke, and as such, these women become the stars of the video. It’s all part of their dance. The lyrics, then, become an interpretation of the expression itself, lamenting the blurred lines of sexuality where rhetorical situations exist beyond traditional subsets (a “good girl” shouldn’t “want it”) and into the vague sensuality of sexuality.

But this is just an interpretive exercise, and an exercise in critiquing Blurred Lines can get as muddled and problematic as the video itself.

I’m not saying the sex-and-women-positive interpretation is the most accurate, nor am I denying the video’s inherit sexualization, participation in the male gaze or potential for harmful interpretation amongst teens/young adults.

The point is that sexuality, and its depiction in pop culture, is complicated. The perspective, theoretical or otherwise, is still bound to certain limits, usually coming down simply to an individual’s interpretation of sex in media, personal ideologies, and relationship with intimacy and their sexual orientation. But that doesn’t mean we should just throw our hands up and say, “Nothing matters, it’s all subjective!” It means we just have to dig a little deeper to find out why.

The Nine Inch Nails song Closer promotes a similar sexual complexity. Some would find the video, while less nude, much more offensive than “Blurred Lines.” Lyrics “You let me penetrate you,” “You let me violate you,” “You let me desecrate you” and “I want to f#(k you like an animal,” lend to obscenity and sexual objectification, but the video and song landed on the critical side of art rather than the exploitation found in Blurred Lines.

It’s important that entertainers express their art and message without degrading women, and it’s equally important to question why women expressing their bodies sexually is considered derogatory or immoral. For the purpose of cultural critique, considerations include how nudity/sexuality is portrayed, for whom the observation is meant, and what message is being broadcast with the express. In general, our societal perspective on sex, sexuality, decency and obscenity challenge what kind of sexual representations we interpret as better or worse than others. But when it comes to society as a whole, we tend to react to sexual complexity with collective extremes.

Exhibit B: Miley Cyrus at the 2013 VMA’s

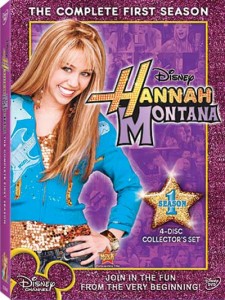

When Miley Cyrus appeared on stage at the 2013 Video Music Awards, Twitter exploded. 306,000 tweets per minute were about Miley Cyrus that night, which was more than the 2012 Super Bowl. People immediately reacted to her extreme sexuality with stupor, disgust and disbelief. How could Hannah Montana become this?!

Our collective reaction to Miley Cyrus’ performance can best be qualified as “slut-shaming.” Slut-shaming, according to the good folks at Wikipedia, is “a label for social control of sexuality by exposing a person to shame for engaging in, or being perceived to engage in, unlawful, abnormal or unethical sexual behavior.”

Take a moment and consider if you perceived Miley’s performance as abnormal or unethical. Many immediately agree that it was, but it’s important to question why. Rihanna, Lady Gaga and Madonna have been blurring the lines of sexual performance art for years, but they aren’t 20 years old and former Disney kids. The world was so shocked by Miley because she’s white, she’s young, and dammit, she should know better!

The reaction to Miley Cyrus was insane, and it paints us the perfect picture of our societal reaction to sex. Take a look at one of the many Buzzfeed articles about her performance. This article compares Miley to 22 things she looked like during her performance, most of which are objectifying jabs at how ugly, slutty and crazy she looked. Take a moment and consider how healthy it is for a society to react to female sexuality like this:

There’s a pretty compelling argument as to how her performance was racist, but when observing Miley herself, it’s interesting to see how the budding, albeit in-your-face and abrasive sexuality of a young woman gets destroyed by critics. Our perception of a ‘slut’ persona has an incredibly negative and consequential aspect in American society, but The Ethical Slut, a sex/lifestyle guide, has been working on re-evaluating sexual promiscuity as empowered positivity. They are trying to reclaim the term for “a woman whose sexuality is voracious, indiscriminate and shameful” to “a person of any gender who has the courage to lead life according to the radical proposition that sex is nice and pleasure is good for you.”*

This article, as mentioned earlier, pertains to adults (+18) and the relationship to sex and pop culture in our consumed media. As such, we won’t be diving into the ethical quandaries of a former teen-star/role-model for a predominately younger MTV demographic. What we can do is critique her, and the collective reaction, as we are: adults. Take a look at the following pictures of Miley Cyrus and decide for yourself which is more liberated/oppressed.

Our attitude toward necessary levels of sexual decency is best observed in the rating system within the Motion Picture Association of American. The MPAA allows one or two f-words in a PG-13 movie, but it cannot be in reference to sex. If it is, it becomes rated R. R-rated movies can allow: sexual themes, frank sex talk, sexualized nudity, tough language, and tough violence. That’s 3-1 sexual guidelines to violent guidelines. An NC-17 rating goes even further, casting the rating upon almost exclusively sexual instances. Why is it much more acceptable to see heads explode and torture scenarios than oral sex? It is easier for the MPAA, and admittedly the rest of us, to digest war making than love making.

Do we need sexual censorship? Absolutely. After all, it’s not all about us. Adults aren’t the only media consumers, and until a person reaches the age of 18, it’s up to their parents and our rating systems to help determine what they can and cannot see. But our interpretation of proper and improper adult sexuality is clearly a larger issue. It’s a battle between multiple cultures across multiple playing fields. Is a “hook-up” culture and sexual expressionism ‘evil’? What makes us more ashamed of sex than any other natural human function? Why do we have vastly different opinions on proper sexuality when it comes to men and women?

How we think about sexuality and where it belongs in society is the greatest crux of pop culture. One person’s obscene is another’s art, and the sexual agency of a people is bound to the opinions of the individual. Cultural sexuality does not have to be a societal calamity. There’s a happy medium in what we accept about sex and how it is interpreted via media, and that’s why “Blurred Lines” is as important an artifact as it is controversial. To converse with each other, share these perspectives and learn from our own interpretations leads us down the road to a further enlightened perspective, and perhaps more understanding can finally lead to a more artistic and fulfilling sexual culture.

*Attwood, Feona. “Sluts and Riot Grrrls: Female Identity and Sexual Agency.” Journal of Gender Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3. November 2007, pp. 233-247.

Related Posts

Pop Culture Week in Review: August 23-29, 2014... August 29, 2014 | Drew Troller

Dear Hollywood… February 5, 2015 | Drew Troller

Pop Culture Week In Review: May 10-16 May 17, 2013 | Drew Troller

18 GIFs to Show How I Feel About Lists of GIFs... February 6, 2014 | Drew Troller

-

September 5, 2013

DrewI get the idea that through a certain lens, the women in “Blurred Lines” are willing participants in celebrating sexuality – that is, they do in fact “want it.”

BUT… aren’t other lyrics still problematic even for eagerly, willingly sexualized women? Can they be excited about being called “the hottest bitch in this place?” Is a compliment for TI to declare that he “had a bitch but she ain’t as bad as you” (nevermind the implied offense to his last paramore)? Or that he’s offering “something big enough to tear your ass in two?”

If anything, that last line (coupled with the scene in the video where balloons give details about the size of Robin Thicke’s genitals) seems to be a celebration of MALE sexuality, and the women are just props (like the balloons). THAT’s why I find this thing objectionable. Sure, maybe the men’s sex partners are and eager sexual partners… but the medium for celebrating that is offensive to both genders.

-

September 5, 2013

Nik HeimachDrew, completely accurate and fair point. I wrote this piece to examine the state of sex in pop culture, and used the Blurred Lines example as a linking point between different observations of how sex, sexuality and gender can be construed across multiple viewpoints. Personally, I agree with you. But that’s why I added this paragraph:

“I’m not saying this is how it is, nor am I denying the video’s inherit sexualization, participation in the male gaze or potential for harmful interpretation amongst teens/young adults. The point is that sexuality, and its depiction in pop culture, is complicated. The perspective, theoretical or otherwise, is still bound to certain limits, usually coming down simply to an individuals interpretation of sex in media.”

While some parts are more obscured than others, it’s pretty obvious that those lyrics in particular are easily sexist/offensive to many.

-

Comments