D-BOX: The Newest Cinematic Experience

Armed with my three pound bag of popcorn and bucket sized soda, I shuffled cautiously into the dark theater like I have hundreds of time before. Squinting through the dim lighting, I ignored the sound of my shoes pulling themselves free of the sticky floor as I made my way to my seat. Despite this well rehearsed process going off without any hint of abnormality, I knew that I was in for a new experience this time around. In fact, I had paid an extra $8 on top of the normal ticket price to ensure that it was anything but standard. Today, I was going to see my first movie from a new D-BOX seat.

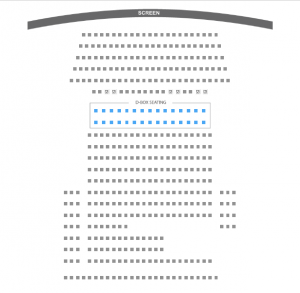

When I first saw the difference in pricing as I viewed the showtimes online, I was a bit confused. Although the time slot was identical, there were two prices from which to choose. The higher one had “D-BOX” written next to the movie title, along with the more common “Atmos,” which is a Dolby sound system. So, I figured that D-BOX must be something like IMAX or 3D, etc. A quick and careless Google search told me that it was a new system from a Canadian company that would take you even deeper inside the film. When I viewed the available seats, there were just two rows to choose from that offered this new experience, positioned towards the middle of the theater. I figured there would be some special speakers integrated into the chair that would deliver surround sound like never before. Oh, how wrong I was.

As the lights in the theater darkened, signally the start of the film, a tutorial played on the enormous screen in front of us. It explained that our unique seats had a small control panel on the right armrest, where we could change the intensity of our experience. You could go with low, medium, or high. I still wasn’t sure exactly what this mystical chair did, which was separated from its neighboring chairs by a few inches, so I did the logical thing and put it on the medium setting. The opening credits of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles started up and I silently noted that I shouldn’t have sat directly in front of a woman and her two kids, because one of those little ones was kicking the back of my seat relentlessly. A series of small, rapid kicks, vibrating my entire seat. How annoying. The kicking subsided and the film began in earnest, with Megan Fox making her way onto the screen with her frozen expression of beauty that she desperately tries to pass off as acting.

An unknown number of minutes in, it was clear that we were setting the stage for some Turtle Power. Thugs moving cargo containers in the dead of night are destined to be attacked by mutant ninjas. As the tension built, the kid behind me started kicking my seat again. The same way he did before, with light kicks that made the whole thing tremble. I was determined to ignore it, but just as a container took a huge hit on screen, the kid lashed out again with a newfound intensity. It was like he had brought his knee up to his chin before driving his heel into the center of my chair, causing a couple popcorn kernels to fall out of my bag. I was about to turn and give his mother a pleading glance when it happened again, perfectly in sync with the action on screen. That’s when I realized… It wasn’t a kid kicking my chair at all. It was my D-BOX seating, delivering a coordinated motion with the action on screen. As henchman started getting thrashed by unseen ninja turtles, I barely registered the visuals of what was happening in the movie. I was too distracted by my seat lurching forward, back, side to side, and generally shaking me like an astronaut in the last 10 seconds of a space shuttle countdown. My right hand scrambled blindly to reduce the setting to low, but even at this level, the vibration and jerking was considerable. After the crime fighting was over and the action dwindled, I sat frozen in my chair, mildly traumatized, wondering if it was safe to reach over and take a drink of soda.

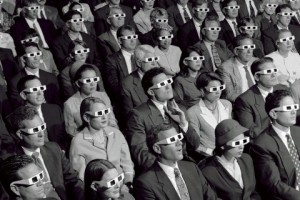

Since the attempts of making films 3D in 1915, we’ve been searching for ways to make the movie experience as immersive as possible. This early effort required impractical equipment that was only available to one viewer at a time and even then left much to be desired, so it was quickly abandoned. It wasn’t until 1952 – 1954 that we entered the “Golden Era” of 3D cinema in America, where viewers were trusted with the disposable anaglyph glasses that had previously only been used on comic books. A handful of films in the 50s delivered this new way of watching movies, but due to technology limitations and reports of eye strain and headaches, the practice faded.

3D movies gained momentum again in the 80s and 90s with shorts and non-fiction pieces, but it wasn’t until James Cameron’s Avatar in 2009 when the real potential was realized. The film brought in over $2 billion worldwide as movie goers packed into theaters to see the planet of Pandora jump out at them from the big screen. The success was well earned, since Cameron had come up with specifications for the new 3D technology back in 2003 for Ghosts of the Abyss, the first full-length 3D IMAX feature filmed with the Reality Camera System, which shot HD video instead of film.

Speaking of which, IMAX (Image MAXimum) is another tactic we’ve used to enhance the visual impact of films. By greatly increasing the size and resolution of the image, stretching it across the viewer’s field of vision, and allowing sound to travel directly towards the audience through thousands of tiny holes in the screen itself, it offers a wonderfully immersive experience. Although this concept was attempted by Fox back in 1929 and again in the 1950s with gimmicks like CinemaScope, VistaVision, and Cinerama, it wasn’t until 1971 that the IMAX that we know today debuted.

Now D-BOX is joining this cocktail of escapism as it utilizes a motion system that synchronizes with the action on screen and delivers 3 axes of movement to the lucky audience member that coughed up a few extra dollars for the privilege of being bucked around like a mechanical bull rider. The effects can be deployed subtly as well. When a van is driving up a mountain road, your seat will incline slightly, to simulate the feeling of moving uphill. With the standard Hollywood trick of breaking silence with a loud noise and action on screen to elicit a jump from audience members, the tactic is that much more effective when you feel a jolt in your seat as well. It’s the same technology used by racing and flight simulators, but it’s even available for home theaters. Check your local listings and you might see it offered on films like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Guardians of the Galaxy, or Expendables 3. I personally enjoyed the experience and look forward to giving it another try, now that I think I’m a bit more mentally prepared for what it brings to the table.

As exciting and fun as my D-BOX seat was, it got me wondering what the future of film holds as we continue to pioneer new ways of intensifying our cinematic adventures. When do we say enough is enough? Are we chasing the dragon when it comes to losing ourselves in a movie theater? Will there be employees whose sole job is to slap us in the face when the hero takes a punch and spray a cold mist from a water bottle when it’s raining on screen?

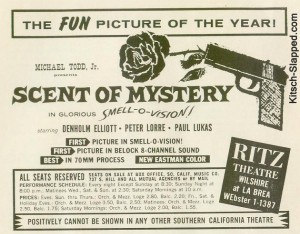

You may chuckle, but let’s not forget that Smell-O-Vision was attempted in the 50s, where odors were released into the theater at strategic times in the film. This concept was actually attempted as far back as 1929, when perfume was sprayed from the ceiling of a New York City theater during a showing of The Broadway Melody. Although I’ve never been in a movie that deployed such techniques, I don’t think it would be my cup of tea. Smells seem to be a much more intimate and personal sensory experience than sight and sound. Overall, the world agreed with me, since Smell-O-Vision was not well received by the public. The odors made a distracting hissing noise when released, didn’t always coordinate with the visuals on screen depending on where you sat in the theater, and even motivated some patrons to sniff loudly in attempts to get the full experience. The brief experiment was thankfully terminated and went on to be listed among the “Top 100 Worst Ideas of All Time” in a 2000 article in Time.

Even 3D, which is being embraced by Hollywood, has its critics. Roger Ebert wrote an entire article on why he hates it, cleverly titled Why I Hate 3D Movies (And You Should Too). He called it a “suicidal” direction for the film business and went on to say that it was “unsuitable for grown-up films” and “limits the freedom of directors.” Whether the effect of 3D is as entirely negative as Ebert made it out to be, it certainly is having an impact on the industry. With studios so enthusiastic about making big budget action flicks with 3D explosions like The Avengers or Man of Steel, some directors are reporting that it’s harder to make movies that don’t fit that mold. George Lucas said that “the pathway to get into theaters is really getting smaller and smaller,” which is obviously true when you look at Steven Spielberg’s difficulty in getting Lincoln made. Despite the solid subject matter of Abraham Lincoln, the phenomenal acting chops of Daniel Day-Lewis, and the near flawless Spielberg at the helm, the film almost ended up on HBO instead of the big screen. In the end, Spielberg had to co-own a studio to produce it.

I suppose you can’t blame the studios from a financial standpoint. You don’t need subtitles when shrapnel and other projectiles are flying off the screen towards your face and your seat is shaking from the epic surround sound or possibly even pitching and rolling if you’re in a D-BOX area. As a result, these action blockbusters sell extremely well all around the world, allowing the studios to earn back their investments that are now more and more commonly estimated in the hundreds of millions of dollars. From an audience standpoint, it’s more about personal preference. Are you a big fan of Wes Anderson? Or do you flock to the theaters for anything Michael Bay cranks out? I fall somewhere in between, since one of my favorite films of all time is Casablanca, but I thoroughly enjoyed my jaw dropping when I first saw the perfected 3D execution in The Avengers.

This gravitation towards effect heavy movies may change the landscape of movies drastically. George Lucas theorized that effect heavy films might end up being more like broadway shows, where there would be less of them produced, higher priced tickets, and they would stay in theaters for a year. Steven Spielberg thinks that after a couple massively budgeted films flop, the paradigm will shift. In the aftermath, you might end up paying $7 for a film like Lincoln, but then have to drop $25 for a Marvel superhero movie. Considering that I paid an extra $8 for my D-BOX seat, I would say he is on to something.

As I pondered the future of film, the most interesting notion to me is that not only will these technologies continue to advance, but they will eventually be so common that watching a 2D movie on a regular screen will be to the future generations what watching a silent black and white movie is to us. The more you’re exposed to the effects, the more they form a cohesive ambience that completely inserts you into the world of whatever film you’re watching. While I honestly didn’t even process some scenes from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles due to the fact that I was so preoccupied with my D-BOX seat tossing me around like a rag doll on a roller coaster, I’m sure that with continued exposure it will become one of the most enjoyable parts of the movie routine. Not surprisingly, Steven Spielberg hit the nail on the head when discussing 3D, saying “once people stop noticing it, it just becomes another tool and helps you tell the story.”

D-BOX is one of those new storytelling tools. Although it at first felt like I was in a theme park instead of a movie theater, I slowly but surely felt it contributing to, not distracting from, the cinematic experience. It’s also a stroke of genius to allow individuals to control the level of motion they feel. I stuck to low for most of the film, since whenever I ventured into the high setting, I was too focused on gripping the armrests for support than what was happening on screen. But I look forward to getting more practice and letting the D-BOX seat run wild at its maximum potential, so long as the lid of my drink is securely fastened.

I’m not sure what the future holds. But it’s a safe bet to say that the term “watching a movie” may fade into obscurity. As the innovations continue to advance, audience members will be doing a lot more than just watching.

Submit a Comment