Book Review & Interview | Marika Josephson on Farmhouse Beer

- David Nilsen

- On April 25, 2019

- http://davidnilsenbeer.com

- FacebookTwitterInstagramLinkedIn

A new chapbook by Scratch Brewing co-founder and brewer Marika Josephson lays out a blueprint for what it means to run a true farmhouse brewery in the 21st century.

“There is an ironic disconnect in craft beer in which drinkers care a lot about beer being made locally but don’t know or don’t care about where the ingredients themselves are from,” said Josephson when I interviewed her for a story for Civil Eats in November 2017.

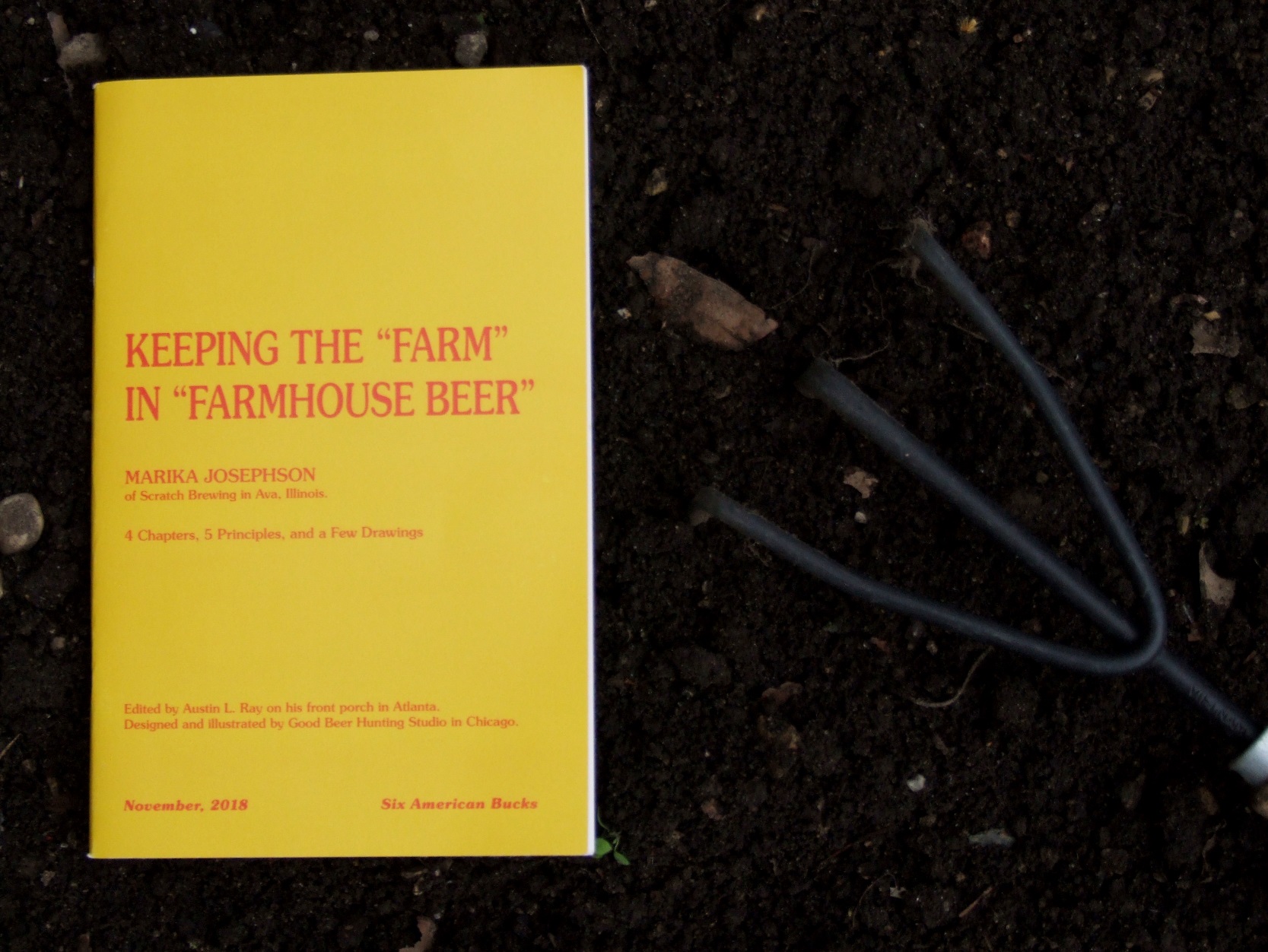

The quote could serve as a thesis statement for her new chapbook Keeping the “Farm” in “Farmhouse Beer”, published by Good Beer Hunting in 2018.

Josephson and business partner Aaron Kleidon have put Scratch on the map by focusing on foraged and locally harvested flavor ingredients, many of them quite esoteric. A trip to the Scratch taproom nestled deep in the southern Illinois woods will find beers made with mushrooms, flowers, wild plants, and every conceivable part of a tree. They take the idea of “local” to a whole new level.

“When we started Scratch I cared a lot about sourcing ingredients locally, but I discovered that that wasn’t the case for many breweries,” laments Josephson today. “It seemed like people were content to just slap a ‘brewed local’ sticker on a window but didn’t care what that meant. What was actually local about the beer inside?”

In this new 42-page chapbook, Josephson lays out a vision for what would make “local” beer truly tied to its point of origin. If you’re going to claim the farmhouse title, she contends, then you need to show your work.

Due to some fanciful and oft-told stories, it is widely passed around as historical fact that the Saison and Bière de Garde styles originated with the need for farms in 19th century Belgium and northern France to provide beer for their seasonal field workers.

Romantic as these tales are, they likely have more to do with twentieth-century brewery marketing than anything that actually happened in nineteenth-century agrarian Wallonia. Was beer served to farm workers? Yes, almost certainly. Was it anything like the “farmhouse ale” at your local brewpub that also slings porters and IPAs? Probably not.

However, because of that strong link in the craft beer imagination between the golden days of rustic brewing and a handful of modern styles, all a brewery needs to do to conjure images of a Belgian farmstead in 1850 is put the word “farmhouse” on a label. Josephson says that’s not nearly enough.

“I think it’s hard for us to understand what beer was like before the Industrial Revolution because it’s hard for us to conceptualize a world in which we’re not globally connected and a world in which our lives and economies are much more centralized in the areas in which we reside,” reflects Josephson.

“Breweries of yore were tied deeply within their communities, and farmhouse breweries largely weren’t commercial enterprises. They shared equipment, they used ingredients grown in a much smaller footprint. It’s better for us to understand that they were living, breathing organisms of their time. I think we’ve romanticized those breweries because we’ve romanticized what we wish they did or wish the beer they made tasted like. But what about agriculture? Farming has also changed dramatically and I think that in general, outside of beer and brewing, it’s important that farming become more small scale again. So, my question is: if we bring brewing back to small communities and small-scale agriculture, what does that whole organism look like in this day and age?”

Josephson believes breweries need to be doing more to support local and regional agriculture.

“The problem is, farmers are fighting big industrial ag the same way craft brewers have fought big industrial beer,” she told me in our previous interview for Civil Eats. “We need to support small farming if we want to see healthier, more diverse, and more flavorful crops.”

Keeping the “Farm” in “Farmhouse Beer” has received some pushback from brewers of recognized farmhouse styles who feel Josephson’s strictures are unrealistic. Josephson is careful to point out however that she never intended her chapbook to be prescriptive or to kick anyone out of the club.

“I think of this piece as a sculpture, of sorts, that is intended to be molded as the state of brewing and small-scale farming moves forward,” she says. “And it was also intended to be open to the realities of other people’s business models, and the state of farming in their areas. It may read as a manifesto because it has some calls to action, but it was never meant to be prescriptive in the sense that I wanted to force breweries or legislators to make hard and fast laws or to rule people in or out. I was simply asking the question: what would an ideal farmhouse brewery be like if we could conceive of one today?”

More than anything, Josephson wants consumers to care about where the ingredients in their beer come from; and for breweries to be honest about those origins.

“I think this [chapbook] is about transparency more than anything,” clarifies Josephson. “I don’t care if you have a brewery in a farmhouse or a warehouse, I just want you to tell your consumers what you’re doing. Not everybody is meant to brew a beer on a farm and that is 100% okay. There is great beer out there that is not brewed on a farm.”

What the folks at Scratch do want to see is recognition that there is a difference, especially economically, between truly local ingredients and those sourced from national brokers.

“There is great mixed-culture fermentation going on in breweries, but that does not mean that beer was made with locally farmed or regionally sourced ingredients,” says Josephson. “And that’s okay! It doesn’t need to be if that’s not your deal. But [local] ingredients are also often more expensive, take longer to process, and may be harder to work with. It’s why some beer is more expensive, so it’s really important for breweries to be transparent.”

Josephson uses the final portion of the book to model that transparency by describing the work Scratch still needs to do to match the vision she’s laid out. Some of the areas she wants to see her brewery improve on will be challenging because of the current agricultural realities in southern Illinois.

Hops and barley have not been grown in their area in a long time; and it will take time to establish those industries on any scale. So, in the meantime Scratch will source those ingredients from their closest growing region. Scratch is also looking into isolating pure fermentation cultures from their property to avoid having to order lab cultures.

Until they are able to figure out satisfactory solutions for water, yeast, and other ingredients that fit their hyper-local guidelines, they will either stop brewing certain beers, or stop referring to beers by style names they are not able to accurately brew. For example, until they can isolate a viable lager yeast strain, they will no longer brew their Oktoberfest Märzen.

Keeping the “Farm” in “Farmhouse Beer” is a fascinating look at what true farmhouse brewing means in the modern era. This book covers what is currently a very small corner of American craft brewing; but it does provide possible avenues for breweries of varying sizes to become more closely linked with local agriculture, returning vitality to small farms and in turn making breweries a more integral part of their local economies.

“I live in a part of the country where agriculture is dying, and so are rural towns and communities. Of all the motivations for writing this piece, one of the largest comes from living in this reality. Brewing is a manufacturing process that connects many parts of an economic organism and we have immense power as brewers when we decide whom we buy our goods from. I think breweries that don’t farm or buy ingredients from local farmers should not call themselves ‘farmhouse’ breweries or say that they make ‘farmhouse’ beer. It’s as simple as that.”

That might sound incendiary, but Josephson is passionate about the intimate link between beer and agriculture.

“I want to preserve the word ‘farm’ for something specific,” she concludes: “farming.”

Feature image courtesy of Scratch Brewing

Related Posts

Hops & Bacteria | How Brewers Use the Antibacterial Properties of Hops... November 17, 2021 | David Nilsen

Book Review | Beer and Racism January 25, 2021 | Ruvani de Silva

Book Review & Interview | Atlas of Beer October 24, 2017 | David Nilsen

Book Review & Interview | Josh Bernstein’s The Complete Beer Course... May 22, 2023 | David Nilsen

Submit a Comment