Ultimate 6er | A Toast to Historical Women of the 1920s

The 1920s was an important decade for women. The 19th Amendment gave us the right to vote in 1920, and what followed was a decade of strength and a search for equality that broke barriers and changed women forever. Women of the 1920s did everything men did, and sometimes they did it better.

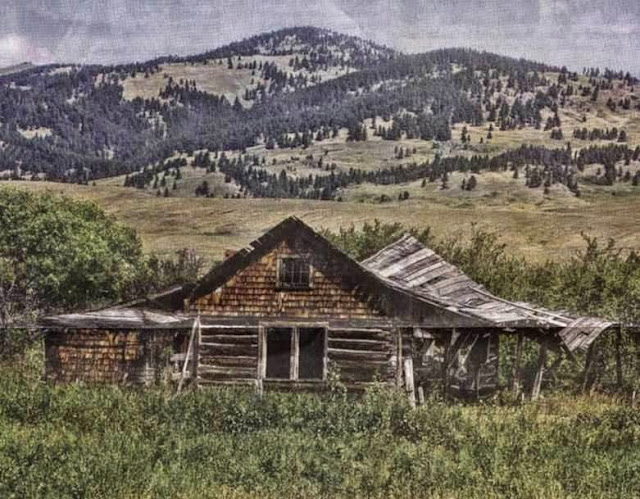

The Bootlegger | Bertie Brown

Paired with: Seneca Lake Brewing Co. | Bertie’s Brown Ale

All the women on our list are pioneers, but Bertie Brown is literally that. She took herself west, homesteading as one of a handful of African American women to do so in the state of Montana – first in Lewiston, then in Brickyard Creek. Living alone, she created a name for herself as independent, resourceful and kind, as well as for making some damn fine hooch. According to locals, she made some of the best – and safest – moonshine in the country, and her parties attracted people from all over the area. In 1933, right as Prohibition was coming to an end, Brown was killed while multi-tasking. Tending to the still while dry cleaning some garments with gasoline, the gasoline blew up in her face, taking her beloved homestead, her still and her life.

Let’s toast that life with a Bertie’s Brown Ale from Seneca Lake Brewing Co.

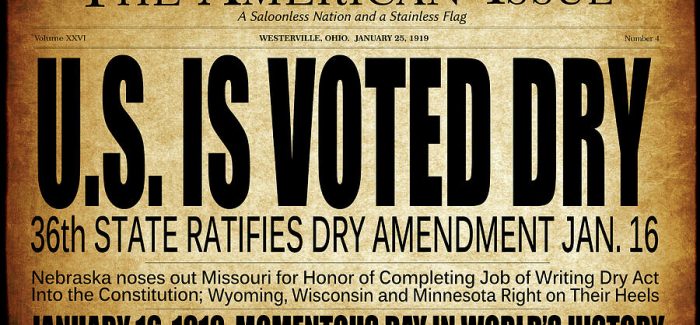

The Prosecutor | Mabel Walker Willebrandt

Paired with: Brewdog | Nanny State

You can’t make a list about women from the 1920s without talking about the first woman Assistant U.S. Attorney General, Mabel Walker Willebrandt. Before Prohibition, Willebrandt had no strong feelings for or against Prohibition, but after the Volstead Act was passed, she made it her life’s mission to see that it was enforced. Her position in the Justice Department under Harding and Coolidge was as the head of Prohibition enforcement, and she did so with gusto.

Willebrandt’s most high-profile conviction was against George Remus, a Cincinnati businessman and infamous bootlegger, but her office tried and convicted tens of thousands of Volstead Act violations during her term. She is also one of only a few Assistant U.S. Attorneys to have argued in front of the Supreme Court over 40 times. She had so much respect and clout in the Republican Party that one journalist floated her as a potential Vice Presidential candidate. Alas, she was not chosen, and her career in politics ended when Hoover passed her over for Attorney General in 1929. She went on to represent the California grape industry and the Screen Actors Guild, and received her pilot’s license, touring the country alongside Amelia Earhart.

As the nation’s first and most ardent prohibition prosecutor, it only makes sense to pair Willebrandt with a Non-alcoholic brew. Since she looked after us so well, why don’t we make it Brewdog Nanny State?

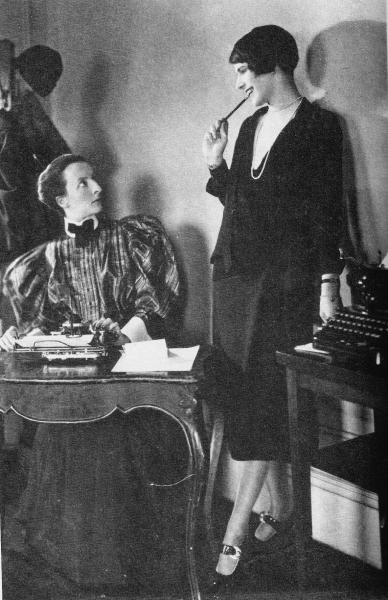

The Flapper | Lois Long

Paired with: Bell’s Brewery | Spontaneous Me

Of all the weekly magazines in the U.S., The New Yorker certainly carries the best reputation for blending sophistication, satire, criticism and commentary, all while featuring beautiful art. It’s a major institution, and for most, they can’t remember a time without it. Back in 1925, however, when the magazine was just an upstart, founder Harold Ross needed a way to give the magazine an edge and drive sales. He found that edge in Lois Long, a clever young writer with a sharp wit, who also happened to embody the quintessential girl-of-the-time – the flapper.

Writing under the pseudonym Lipstick, Long reviewed speakeasies across New York City. Her biting remarks on everything from the music, booze and fashion were wildly popular, and her column “When nights are bold,” later renamed, “Tables for Two,” put The New Yorker on the map. She spoke of the world of speakeasies in a glamorous light, and redefined fashion criticism, making it elegant, clever and fun. Her column featured criticisms of elected officials as well, particularly those who conducted raids on her favorite haunts. She became the flapper archetype, and she was as unapologetic about it as possible.

Lipstick’s identity remained a secret until 1928, when she revealed herself in her wedding announcement to cartoonist Peter Arno. It didn’t stop her though. She continued writing “Tables for Two” until 1930.

A wild life deserves pairing with a wild ale, especially since it’s meant to be served in a champagne flute and can’t be controlled. Let’s go with the final ode to another writer, Walt Whitman, and toast Lipstick with Bell’s Brewery Spontaneous Me.

The Agent | Daisy Simpson

Paired with: Hooch

Where Lois Long was full of class and youthful rebellion in NYC, across the country another sort of woman was coming up and making news. Daisy Simpson spent her youth in the dreaded saloons and dive bars of San Francisco, taking illicit drugs and gallivanting with gangsters and other low-level bad guys. Around the first world war, she got clean and joined the morals squad of the San Francisco police department. From there, she became a field agent for the Treasury Department.

Simpson’s seedy past gave her an edge other agents – both male and female – did not. Unpolished and rough, she was easily able to go undercover, often using disguises, to bust distributors and bootleggers. She became known in the press as “Lady Hooch Hunter,” and was so good at her job that she worked not only in San Francisco but also in Chicago, Baltimore, New York and Milwaukee.

In 1925, the San Francisco Treasury Department banned women from working as field agents, and Simpson quit the agency altogether, unwilling to work a desk. After that, she went back to her old ways and was arrested for drugs in March 1926. While in custody, she shot herself in the stomach, hoping to commit suicide. However, she survived, and shortly after faded into obscurity.

How do you think the Lady Hooch Hunter would have felt if she discovered Hooch?

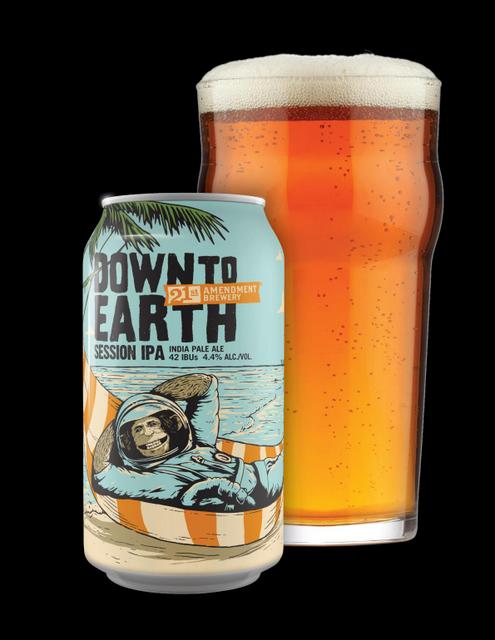

The Organizer | Pauline Sabin

Paired with: 21st Amendment Brewery | Down to Earth

Women played a pivotal role in instituting the 18th Amendment, so it only made sense that to get it overturned, women needed to take charge. The most vocal of the women who led that charge was Pauline Sabin, a politically connected New York socialite who’d made a career of organizing the women in her circles. A staunch Republican and proponent for women in politics, Sabin took an active role in the party from the moment the 19th amendment was ratified. She helped found the Women’s National Republican Club, and participated in multiple Republican conventions as New York’s first women representative on the Republican National committee. During the early 1920s, she encouraged women to engage in all aspects of politics, and to not get caught up in a single issue.

Sabin initially supported Prohibition, thinking it would help her sons and alleviate the country of the alcohol problem. However, as Prohibition carried on, it became clear to her that rather than keeping young people from drinking, it encouraged them to flout the laws, drink younger than ever before, and disrespect the constitution. She also disliked the hypocrisy of politicians of all ilks who were politically dry, but personally wet – voting for stricter laws and then celebrating the vote with a drink.

In 1929, she founded the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, a type of single-issue organization she spoke against in the past. The organization was non-partisan, partnering with any politician willing to repeal the 18th Amendment. Taking issue with the WTCU and other women’s temperance groups who claimed to speak for all women, Sabin proved them wrong when, in less than two years, the organization grew to 1.5 million women. The WONPR believed that making booze legal again would protect families, lessen crime, and restore respect for the law.

In 1933, with the help of WONPR and other repeal groups, the 21st Amendment was ratified, effectively ending America’s Prohibition. Sabin never quite lost her interest in politics, campaigning for Fiorello La Guardia, directing volunteers for the American Red Cross, and joining the First iteration of the Committee on the Present Danger in 1950. She died in 1955.

For leading the charge to bring rationale back to the states, let’s raise a toast with Down to Earth Session IPA from 21st Amendment Brewery. It’s not quite 3.2 beer, but it’ll do.

The Banker | Maggie Lena Walker

Paired with: Harlem Brewing Co. | Renaissance Wit

Maggie Lena Walker was revolutionary long before women had the right to vote. Born in Richmond, Virginia in 1864 to Elizabeth Draper, a former slave and assistant cook at the home of abolitionist and spy Elizabeth Van Lew, Walker moved forward in life taking every opportunity she could to improve herself and the lives of other African Americans.

As a teenager, Walker joined the Independent Order of St. Luke, an organization that provided health insurance, burial benefits, self-help and support to Black Americans. She trained to be a teacher and taught for three years before marrying in 1886. From there, she focused on her family and began to rise through the ranks of the IOSL. She became Right Worthy Grand Secretary, the highest leadership position within the national organization in 1899 and saved it from collapse, organizing membership drives, and increasing the membership to 100,000 in over 20 states.

Through the organization, Walker published a newspaper, The St Luke’s Herald; began a department store, the St. Luke Emporium; and started a bank, St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. By opening the bank she became the first African-American woman to charter a bank and serve as its president in the United States. She used these three organizations to promote success in Black communities – providing loans, savings and checking accounts, and employing mostly Black women to run all three businesses. By 1920, the bank had helped finance over 600 homes and businesses for Black families.

St. Luke Penny Savings ran successfully throughout the 1920s, and beyond. After the crash of 1929, Walker merged the bank with two other African American banks in Richmond – Second Street Savings Bank and Commercial Bank and Trust – to become Consolidated Bank and Trust. The bank remained independently until 2005.

In addition to her work with IOSL, Walker served on the executive committee of the National Association of Colored Women and more than 10 years on the board of the NAACP. Around 1915, she was diagnosed with diabetes, and her health deteriorated to the point that by 1928, she was relegated to a wheelchair. Her mind was just fine, however, and she continued her work, serving as President of St. Luke Penny Savings, and then as Chair of Consolidated Bank and Trust until her death in 1934.

How do you celebrate a woman who accomplished so many firsts and did so much for her community? How about with a beer from the first Black woman-owned brewery in the U.S. – Renaissance Wit from Celeste Beatty’s Harlem Brewing Company.

Submit a Comment