Cullen-Harrison Act of 1933 | National Beer Day

“I think this would be a good time for a beer,” exclaimed Franklin Roosevelt after signing the Cullen-Harrison Act on March 22, 1933. Though the passage of the 21st Amendment in December 1933 fully ended the nation’s temperance experiment, the Cullen-Harrison Act allowed for the legal sale of low-alcohol beer (and wine). It went into effect on April 7, 1933, a day we commemorate as National Beer Day.

The 1919 ratification of the 18th Amendment prohibited the buying, selling or production of “intoxicating liquors,” but the amendment didn’t explicitly define “intoxicating.” Therefore, Congress had to provide additional legislation, which they did in 1920 — the Volstead Act. Shocking many who assumed beer would be safe from Prohibition laws, the Volstead Act declared intoxicating liquors as any drink exceeding 0.5% ABV. Happy days were no more.

What followed was an era of speakeasies, smugglers, a mob-controlled liquor industry, and an otherwise fruitless effort to turn the United States into a dry country. So, in 1933, fresh off his March inauguration, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the new Congress prioritized the repeal of Prohibition. Of course, by then, the nation was mired in the struggles attached to the Great Depression. Given the country’s economic plight, it seemed illogical to Roosevelt that the government would spend money on policing illegal alcohol activities while simultaneously watching (tax-free) liquor-sale dollars flow to the very people they were trying to apprehend — the mob.

Still, the wheels of democracy move slowly. So, rather than wait for the passage of what would become the 21st Amendment, the President requested on March 13, 1933, that Congress (many of whom campaigned to end Prohibition) develop a plan to adjust the Volstead Act.

“I recommend to the Congress the passage of legislation for the immediate modification of the Volstead Act, in order to legalize the manufacture and sale of beer and other beverages of such alcoholic content as is permissible under the Constitution; and to provide through such manufacture and sale, by substantial taxes, a proper and much-needed revenue for the Government. I deem action at this time to be of the highest importance.”

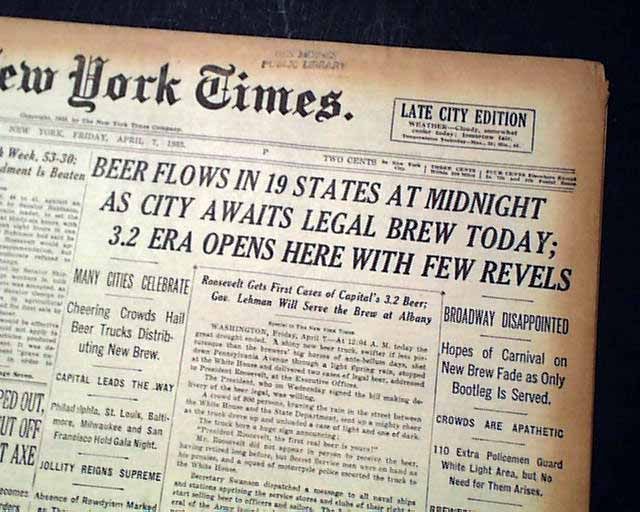

Congress acquiesced by passing the Cullen-Harrison Act on March 21 (named for its sponsors, Representative Thomas H. Cullen and Senator Pat Harrison), which legalized the sale of wine and beer under 3.2% ABV. The legislation went into effect on April 7, 1933, but only for nineteen states as each state had to create legislation to make it legal. As soon as the 3.2% ABV beer flowed in those first states, crowds gathered outside breweries and bars to celebrate the occasion.

In St. Louis, the Budweiser Clydesdales paraded through the streets, fitting because it was primarily large brewers who possessed the resources and capital to re-open after more than a decade of closure. Big beer would profit from the memory of Prohibition, too. They benefited from the fact that beer sold during Prohibition, often by the mob, either tasted poorly or made people sick. As a result, people gravitated towards name brands they felt they could trust. And, those breweries had the resources to distribute and market the beer effectively, too. It proved to be the first of several factors that led to a substantial decline in breweries from 800 in the mid-1930s to less than 100 by the 1980s.

However, in 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed a bill allowing homebrewing, thus repealing one of the final Prohibition-era federal laws on the books. As a result, a new wave of brewers and beer enthusiasts emerged, helping (in part) to create the modern beer boom with nearly 8,000 breweries operating by 2020. Happy days, happy days.

And with beer enthusiasm comes beer holidays. The genesis of National Beer Day came in 2009, a day set aside to commemorate the enactment of the 1933 Cullen-Harrison Act. Although one could argue, it’s just a day to celebrate beer and the brewers who provide us with our favorite libation. Regardless of how one views the holiday, it’s a great day to have a beer — including craft beer, which was not always possible.

Sources / Further Reading:

- National Constitution Center “The constitutional origins of National Beer Day.” Constitution Daily. constitutionalcenter.org. 2021. https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-constitutional-origins-of-national-beer-day/.

- Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2010.

- Ogle, Maureen. Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer. Orlando: Harcourt Books, 2006.

- The Mob Museum. “Prohibition Profits Transformed the Mob.” Prohibition: An Interactive History. themobmuseum.com. https://prohibition.themobmuseum.org/the-history/the-rise-of-organized-crime/the-mob-during-prohibition/.

- Powers, Mathew. “A Pint of Liberty.” M.A. Thesis. Dekalb: Northern Illinois University. 2013.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. Message to Congress on Repeal of the Volstead Act. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/207797.

Feature Image: A crowd gathers as kegs of beer are unloaded in front of a restaurant on Broadway in New York City, the morning of April 7, 1933, when low-alcohol beer is legalized again. (2018 AP Photo, via https://www.facebook.com/APImages/.)

Submit a Comment