Texas Keeper Cider | Harrison

Cider nerds and beer nerds have a lot in common, especially when it comes to appreciating, celebrating and recreating historic beverages. As the beer world grows in appreciation for heritage styles like Roggenbier, Lichtenhainer and Grodziskie, over in ciderland, heritage apple varietals are big news, and the Harrison, with its fortuitous origin-story and serendipitous rescue from extinction, is the rock star of heritage heirloom apples.

Over the last few years, single-varietal Harrison ciders have been making a comeback across the US, but Austin’s Texas Keeper Cider are the first Texans to make their own version — an exquisite blend of 2021 and 2022 harvests, sourced from a 5th generation grower in upstate New York, with the 2021 batch wild-fermented and aged in stainless steel tanks. This limited-edition release showcases the distinct qualities of the Harrison that made it among the most popular cider apples in the US in the 18th and 19th centuries through the prism of modern blending techniques. But before we dig into the cider itself, here’s a quick run-down on the turbulent history of the Harrison apple.

The apple originates from Newark, New Jersey, and is named for Samuel Harrison, a businessman and entrepreneur, among whose many concerns was a cider mill for which he planted a range of apple seedlings, one of which grew to produce Harrison apples sometime around 1713. Planting a seed and growing a tree might not sound like an especially unusual or exciting way of producing an apple, but, as Lindsey Peebles of Texas Keeper Cidery explains, contrary to popular belief, this is not actually how most apple varietals are produced. “The typical way growers propagate apples is to take cuttings from the parent tree that are then grafted onto apple rootstock – grafting produces the genetically same apple as its parent,” she explains, “But chance seedlings are in and of themselves a wonderful stroke of fate: when you plant an apple seed, you never know what you’re going to get, and the vast majority of the time the apples produced are total spitters.” The Harrison stood out immediately as an exception to this rule. “When it happens that we humans stumble upon an apple with a complex flavor, high levels of tannins, acidity and sugar, like the Harrison, what luck!” Peebles exclaims.

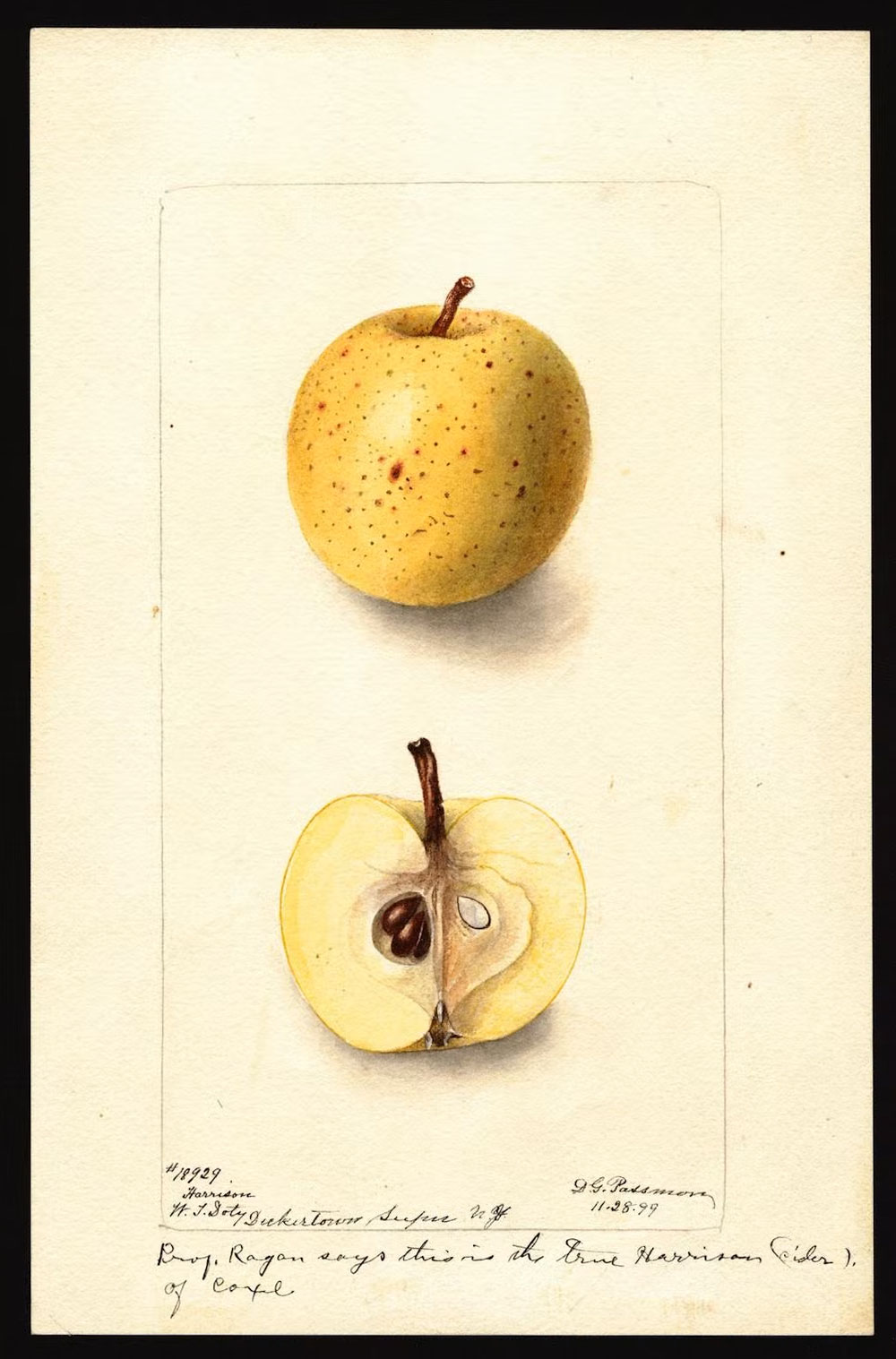

Indeed, Harrison cider grew quickly by word of mouth, and was reported to be a favorite of George Washington, who even preferred it to his native Virginia crab apple cider. By the early 19th century, Harrison cider was being advertised in the New York Post, and its popularity soon spread across the US, reaching California by the 1880s, and was even shipped to the West Indies. However, between the waves of immigration to the US from Central Europeans who brought their beer culture with them in the mid-19th century and the growing power of the temperance movement going in the 20th century, cider began to lose market share, and the Harrison fell into decline. As New Jersey industrialized, its apple orchards disappeared, and Harrison cider became a niche product, falling almost out of existence until 1976, when Vermont orchardist Paul Gidez rediscovered the Harrison, having read about it in William Coxe’s 1817 A View of Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider, the first book to catalogue American fruit trees after the Revolution. As luck would have it, Gidez managed to swipe a cutting from a rare specimen just days before the tree was cut down. Gidez shared his scions with another heirloom apple nurseryman, Tom Burford. Between their efforts, the Harrison is now back. Trees take between four and twelve years to produce apples, so they are still considered something of a delicacy, and are saved for the single-varietal production for which they are so perfectly suited.

In A View of Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider, Coxe describes Harrison cider as “The taste pleasant and sprightly, but rather dry — it produces a high colored, rich, and sweet cider of great strength,” noting that it sold for upwards of $10 per barrel in New York — a hefty sum at the time. But you get what you pay for, and the same is true of contemporary Harrison cider, which shines a sophisticated complex light over its commercial-apple companions.

Texas Keeper are known for their complex, sophisticated high-end small-batch ciders, so when the opportunity arose to make their own single-varietal Harrison they jumped on it. “We’re driven more by curiosity and the craft part of cidermaking,” Peebles explains. “The thought process is more like, ‘Our grower has Harrison apples, a once-prized cider apple that was at one point believed extinct? Heck yeah!’ And because it felt like we had such a special apple, we were going to want to keep it all on its own if at all possible – luckily its reputation bore out and making a Harrison single varietal was not at all a hard choice.”

The resulting cider is a joy to imbibe. It pours a deep golden color with high effervescence, its crystalline delicate bubbles reminiscent of champagne as they stream cleanly upwards, popping on the tongue, releasing bursts of tart, dry, funky delight that fully coats the mouth, slowly ebbing away to make you reach for another sip. The bright mineral-crispness of the citrusy bitter-sharp fruit demands that the Harrison be served fully chilled and it has a long finish that’s pure apple skin. Underlying notes of kiwi fruit and skin add to the Harrison’s mystique and there’s a faint floral undertow coming through from mid-glass with some soft cantaloupe too. The problem with most really special beverages is that it’s hard to drink them slowly and the Harrison is no exception — you keep going in for more and its full tannic aroma continues to fill the glass as it’s contents abate. Try not to audibly smack your lips.

While there’s no doubt that the Harrison is a beautiful single-varietal specimen, Texas Keeper’s expertise at their craft plays no small part in the end result, particularly the clever combination of wild and cultured ciders from two different harvests. “We put a lot of emphasis on the blending stage of cidermaking — it’s at least a couple of blending trials with several palates involved, to get the balance we want,” says Peebles. “The main variable in blending is the apple variety of course, which is why we ferment our varieties separate and blend later but yeast strains are another variable arguably as impactful.” The use of wild fermentation is becoming increasingly common in cidermaking, opening new doors for cidermakers as it has in the beer world, and the combination of Central Texas microbes with a Northeastern heirloom apple has yielded very special results.

Texas Keeper Cider’s Harrison small batch single varietal cider is available from their taproom, locally in stores around Central Texas, and from their website, which ships to 39 states.

Cider provided by Texas Keeper, opinions writer’s own.

Submit a Comment